Why Ruggles Mine Should be Saved

The signs announcing Grafton's Ruggles Mine are a fixture along Route 4 and 104. They’re painted brown and look a little homemade. Some announce the former tourist attraction as “world famous,” which maybe convinces some, but may come across as a little grandiose.

And yet, Preservation Alliance field service representative Andrew Cushing notes that his grandparents love to tell a story about their vacation out West in the 1970s when someone pointed to their station wagon’s wooden rooftop cargo box emblazoned with “Grafton, NH” and shouted across the parking lot, “Hey, Ruggles Mine!” Those "world famous" brown signs seemed a little more believable after that.

After closing its door as a visitor destination in 2016, the future of Ruggles Mine has remained in limbo. Several price cuts failed to attract serious bids and the site has been subject to trespassing and vandalism – Grafton’s sole police officer can attest.

The New Hampshire Preservation Alliance approached officials in the N.H. Division of Parks and Recreation several months ago and proposed the site become the newest state park. While it would not be a conventional park, it would be a unique offering that combined historical, geologic, and natural features as well as incredible scenery. Its 235 acres is mostly forested, is adjacent to the Forest Society’s Grafton Pond Reservation and Blodgett Forest, and it sits squarely within the Quabbin to Cardigan Initiative.

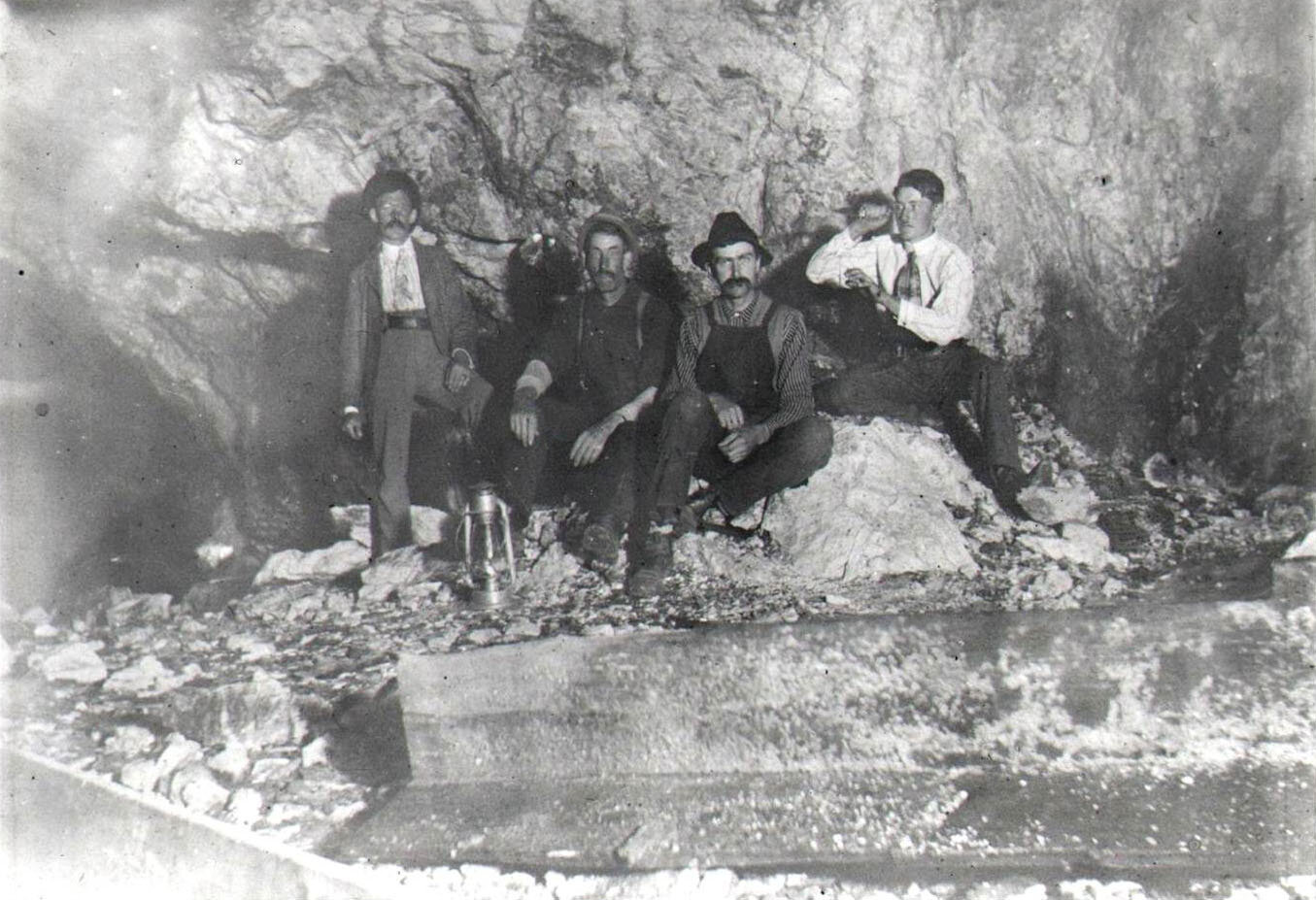

1911 crew at Ruggles Mine. Courtesy Grafton Historical Society.

The mine has tremendous historical value, not only to the state but the country. New Hampshire may be the Granite State, but the western hill towns of the state were especially known for their mica mines. Mica mines were common in the towns of Alstead, Gilsum, Grafton, and Groton, where the material would be used in lanterns and stove windows – and later, for electrical insulators.

Ruggles was the first mica mine in the United States. (In fact, before the Civil War, New Hampshire produced all of the mica in the United States.) Samuel Ruggles started mining in earnest in 1803, though records suggest that mica had been discovered in Isinglass Mountain as early as the 1770s. (Samuel Ruggles was actually more of an investor than a farmer or miner.) What ensued was over 150 years of active mining during which Ruggles was the largest mica and feldspar mine in New Hampshire.

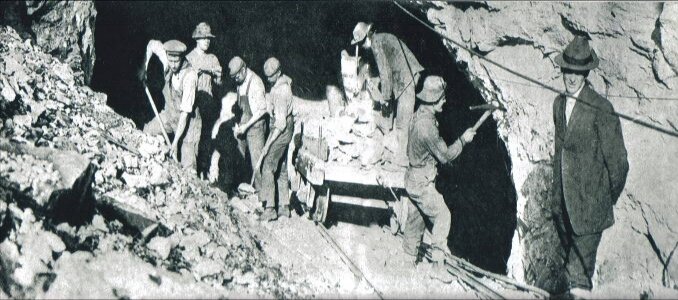

Courtesy Grafton Historical Society.

The result was a scarred landscape with spectacular pegmatitic arches. When the mine closed in 1962 due to changes in the global markets, the site was purchased as a tourist attraction. Between 1962 and 2016, the mine welcomed rock hounds and curious families alike, with the draw being the ability to hammer away in hopes of finding gems or rocks.

The Preservation Alliance is pleased that the N.H. Division of Parks and Recreation is actively exploring whether the property meets its mission as well as financial and operational issues. New Hampshire has nearly one hundred state parks, including mountain peaks, lakeside beaches, gorges, and historic sites. Because the state’s park system is largely self-funded, new additions are rare. (Jericho Mountain State Park in Berlin is the newest member of the park family, purchased in 2007.) Ruggles could provide income to the state park system – and creative types have already suggested using the mine for concerts or outdoor art exhibits, such as the one created by the Revolving Museum in 2017.

Such an endeavor will take time, money, and imagination. The result, however, will be an important landscape preserved for the future. Support for such an initiative can surely be...mined.

The view from the parking lot at Ruggles Mine affords northerly views toward Mount Cardigan.