Precious Metals: The Status of NH's Metal Truss Bridges

Woodsville is the perfect place to witness the evolution of bridge construction. Perched above the junction of the Ammonoosuc and Connecticut Rivers, the village grew like gangbusters after the coming of the railroad in 1853 and the relocation of the Grafton County seat there in 1889. Its brick blocks and Victorian homes speak to these decades of prosperity. And if the wind blows just right, it’s not too difficult to smell a scent that speaks to the area’s bucolic landscape: manure.

Standing downtown today, there are three bridges within a few minutes’ walk. Most covered bridge lovers will recognize the Haverhill-Bath Covered Bridge off of Route 135. Built in 1829, it’s purported to be the oldest covered bridge in America. In 1999, the bridge was closed to vehicles and relegated to foot traffic only. The NH Department of Transportation (DOT) bypassed the historic bridge with the steel stringer and concrete deck variety, the kind of bridge that blends so well into the roadscape you don’t always notice you’re crossing it.

If you feel like venturing across the Connecticut River, though, Route 302 takes you through a 1923 trussed arch bridge. Painted Lady Liberty green and resembling a larger-than-life-sized Erector Set, the Veterans Memorial Bridge is of a variety even rarer today in New Hampshire than the 1829 covered bridge.

Vietnam Memorial Bridge, Woodsville.

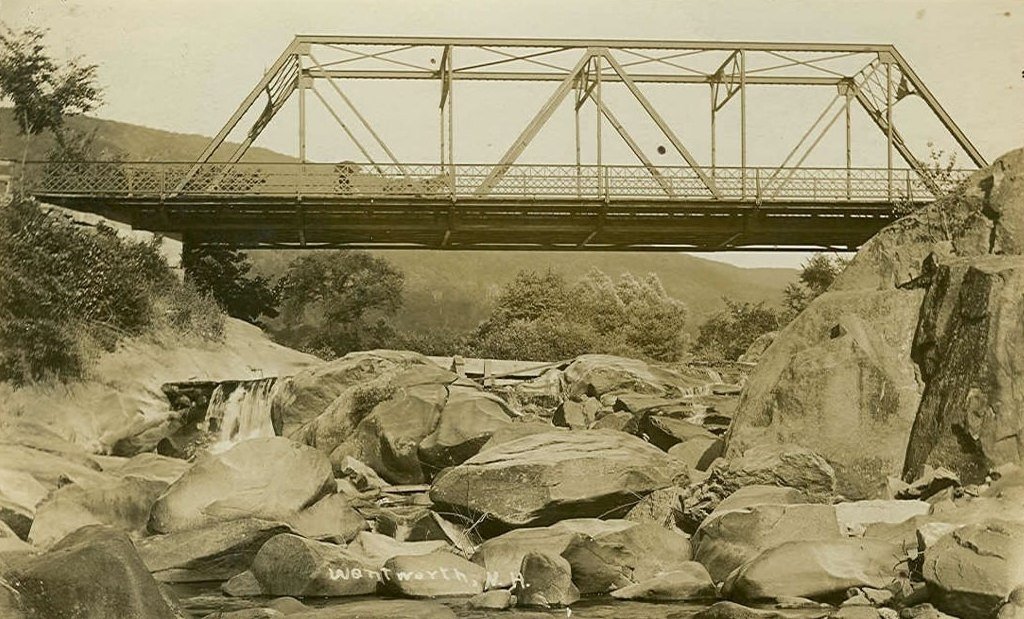

It’s true. There are 54 historic covered bridges (including four railroad ones), with an additional 17 constructed since 1957. Today, the DOT counts 51 metal truss bridges, excluding the recently demolished Lilac Bridge in Hooksett and one in Wentworth. Subtract from that list planned demolitions of metal bridges in Lancaster, Newport, and Henniker, and only 48 remain. (It’s worth noting that the metal bridge list from DOT does not include railroad trusses.)

The alarming rate at which metal bridges were coming down prompted their placement on the Preservation Alliance’s Seven to Save list in 2008.

Perhaps no metal truss bridge put up a bigger fight for survival than the Arch Bridge between Walpole and Bellows Falls, VT. Built in 1904 and the first of its kind to combine the suspension and arch configuration, the single-spanned behemoth’s planned demolition drew 4,000 spectators in 1982. The first two attempts to implode the "structurally-unsound" bridge failed. According to a Christian Science Monitor article, “Absolutely nothing happened. Like an actor who has forgotten his exit cue, the bridge stood frozen - anticlimactic and sound.”

It took two more days, two more blasts, and a crew with blow torches to weaken the Arch Bridge. In the end, the bridge’s admirers didn’t know what to think. Part of them mourned the loss of the remarkable bridge, but another part of them celebrated the bridge’s defiance.

Arch Bridge between Walpole and Bellows Falls, VT. Demolished (not without a fight) in 1982. HAER image, Library of Congress.

While the loss of metal bridges has worried some for decades now, it's largely been a silent phenomena. “It’s easy to love a covered bridge. It’s a bit harder, it seems, to grow attached to the successor of the covered bridge,” wrote former State Architectural Historian Jim Garvin in a 1998 article.

Why are metal bridges not loved like their wooden, covered brethren?

Part of it is the perception of rarity. New Hampshire once had over 400 covered bridges, and while some were lost to ice jams and fire, most were razed with the same rationale we use today with metal bridges: they’re obsolete, expensive, ugly. But with rarity comes appreciation. As time passes, we are more likely to reconsider what is a community asset with historical value. Remember there are fewer metal truss bridges in New Hampshire today than covered bridges. They are rare!

Another part is expense. Jill Edelmann, Cultural Resources Manager with DOT, says that “Maintenance is huge. Painting and cleaning metal bridges takes time given all the surface area.” To boot, metal in salty environments like our winters does not hold up well. Many metal bridges are also owned by towns, which have an increasingly difficult time paying for infrastructure like bridges. Some communities have negotiated that metal bridges remain for pedestrians, but such a use without a maintenance funding plan can lead to demolition by neglect.

The 1937 Justice Harlan Fiske Stone Bridge in Chesterfield was bypassed by the larger bridge (right) in 2003. A nonprofit group formed to beautify and maintain the pedestrianized bridge, but it dissolved in 2016.

The truth is, however, that many covered bridges are also owned by towns, and maintenance isn’t cheap for them either, but we acknowledge their importance and treat them accordingly. Imagine blowing up the Windsor-Cornish Covered Bridge. When arsonists succeeded in destroying Plymouth’s Smith Bridge, Swanzey’s Slate Bridge, and Newport’s Corbin Bridge in the early 1980s, they were all reconstructed because their loss was considered too great.

Lastly, metal bridges simply don’t conjure up romantic notions like covered bridges do. They’re on our postcards, Christmas cards, postage stamps, calendars, and Currier and Ives lithographs. A quick search on Instagram and Flickr reveals that covered bridges have nearly thirty times the number of photos as metal truss bridges. You don’t have to be an engineer to find the beauty in metal bridges, but clearly these endangered structures have yet to convince the general public of their magnificence.

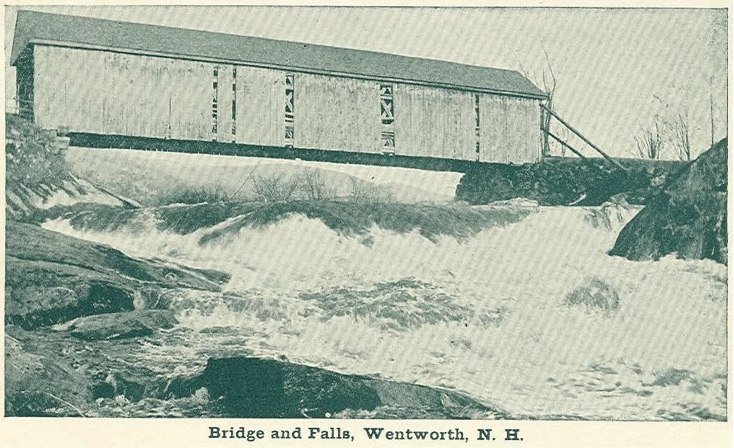

Ironically, many of the metal bridges now endangered replaced covered bridges during the “Good Roads” movement across America starting in the late 1800s. In Wentworth, a 1909 Warren through-truss bridge replaced a covered bridge, only to be replaced itself with a covered bridge in 2016 (in fact, the former Goffe’s Mill Covered Bridge from Bedford). Some saw the newest replacement as picture-perfect, while others lamented the loss of the metal bridge which had come to define the village for nearly a century.

In 1963, NH passed a law recognizing covered bridges as historic and eligible for state aid for rehabilitation. Public hearings are required for any covered bridge’s proposed demolition. Since the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966, thirty-three (or about two-thirds) of our covered bridges have been listed to the National Register of Historic Places. That push in the 1960s, aided by bicentennial fervor, helped shape our modern-day perception of covered bridges.

We need that attitude now for metal bridges.

The Meadow Bridge in Shelburne was added to the National Register in 2003. The next year, it was moved to shore, where it still sits. The other National Register metal bridges include the Piermont-Bradford Bridge, Orford-Fairlee Bridge, and Chichester's Pineground Bridge.

Our task, then, is to appreciate our surviving metal truss bridges. We can learn about the types of trusses that exist. We can get more listed to the National Register of Historic Places – only four are currently listed. We should create a numbered marker program like the covered bridges and celebrate those still standing. Laura Black at the NH Division of Historical Resources (DHR) recommends that you let your selectboard and DOT know your feelings toward the preservation of your community’s metal truss bridges. Make noise to make sure they’re maintained regularly and provide alternatives to demolition. Starting in September, the DOT is hosting nineteen public hearings for the next ten-year transportation plan. If you have a favorite metal truss bridge, consider attending a meeting.

Meanwhile, an update to New Hampshire’s Historic Bridge Inventory is currently being developed by DOT in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the DHR. The products of the update will provide FHWA, DOT, DHR, municipalities, and the preservation community with more concrete understanding about the status of our state’s stone, covered, and metal bridges and how to best steward and manage them in balance with current transportation needs.

Back in Woodsville, the Vietnam Memorial Bridge is here to stay for a while, after rehabilitation in 2003. It now holds the distinction of being the oldest extant steel arch bridge across the Connecticut River. Let’s make sure it stays that way.