Bill Noble's Spirit of Place in a New England Garden

The landscape surrounding a historic house has its own history too. Choosing to restore or rehabilitate a historic landscape, or create a compatible new landscape and gardens, can enhance both the value of the property and your enjoyment of it. And there’s great personal satisfaction along the way.

For tips on this process, we turned to garden designer and garden preservation professional Bill Noble. He believes that “a garden is never created in a vacuum but is rather the outcome of an individual’s personal vision combined with historical and cultural forces.” Bill has worked at some of New Hampshire’s finest historic gardens. He got his start at St. Gaudens National Historic Park in Cornish, and moved on to restoring the extensive gardens at the John Hay Estate at The Fells on Lake Sunapee. As Director of Preservation for the Garden Conservancy, he was instrumental in the preservation and restoration of dozens of gardens throughout the United States. (www.gardenconservancy.org). He now designs and restores gardens for private clients.

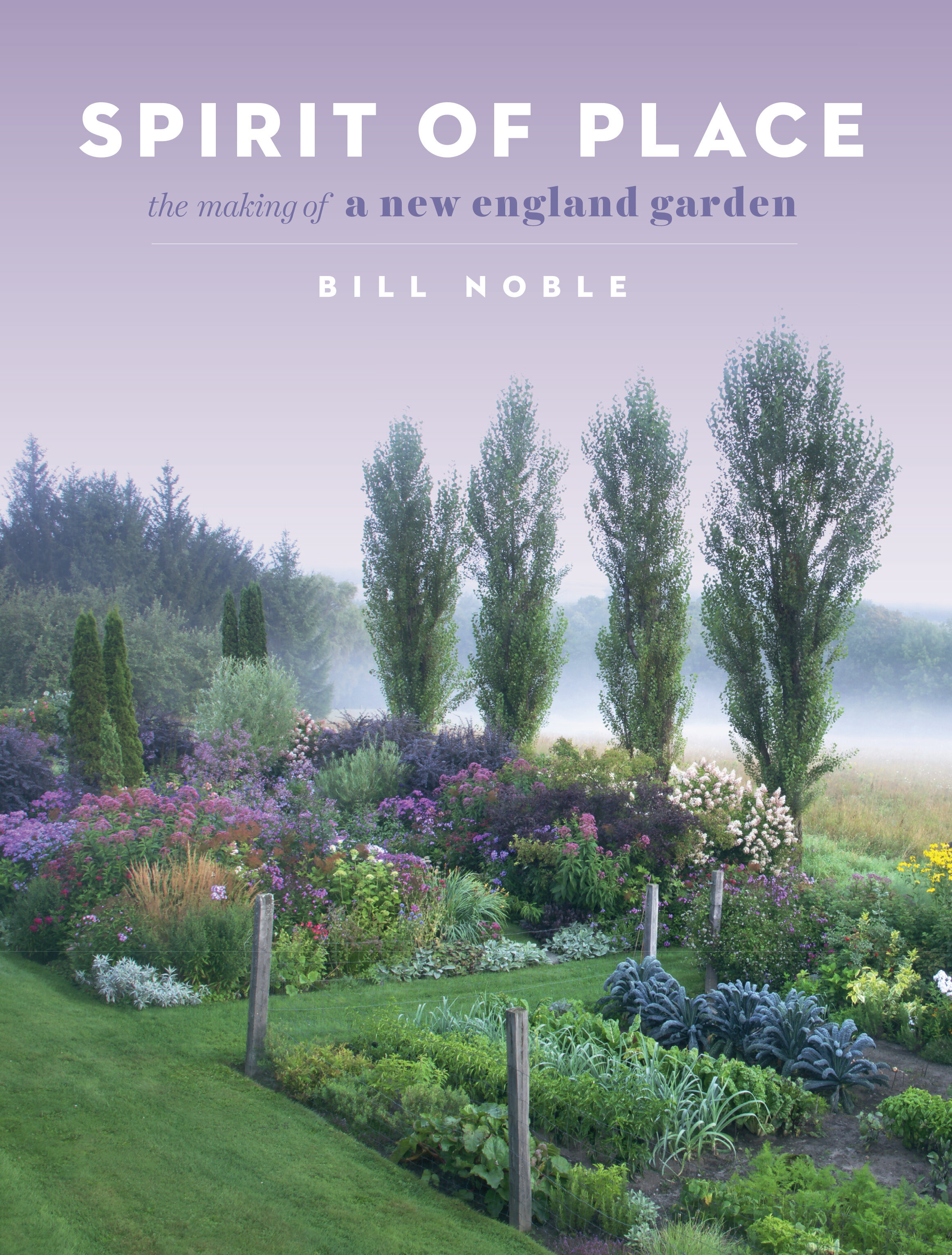

Bill’s recently-published book, Spirit of Place: The Making of a New England Garden chronicles his own 35 year journey to create a garden on a former hillside dairy farm in Norwich, Vermont, just across the border from Hanover, NH. Bill’s remarkable garden is included in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archive of American Gardens and has been featured in Martha Stewart Living, House & Garden, The New York Times, Washington Post and the Garden Conservancy’s Outstanding American Gardens.

Bill strongly urges people not to make any drastic outside changes during their first year in an old house. Observe the landscape through the seasons, noticing patterns such as where the snow lingers, areas of sunlight and shade, soil types, and landscape features like views, streams, and fields. Identify plants that are already there: spring bulbs, specimen plantings, fruit trees or bushes, historic trees, shrubs, and perennials.

Record What Is There and Draw a Base Map

Then he advises doing some research and documenting how the spaces of your property were used in the past. Gather old photographs and maps if you can. Talk to neighbors. In addition to natural features, document all elements of the built landscape--barns, sheds, and other outbuildings, foundations, stone walls, fences, walks and pathways, former garden areas, even utilitarian places such as a clothes line area. Then make a map, drawn to scale, of your existing conditions.

Now for the fun part.

Figure out What you Want

Bill suggests a planning process that will require you to consider questions such as: What do you have to work with? What other elements do you want to add (seating, sculpture, etc). While his garden includes acres of open space, if yours is an in-town location, you can work with the streetscape, existing trees, buildings and structures on a smaller scale.

Ask yourself these questions:

1, How does the garden relate to the larger landscape? What are the focal points? What needs to be screened?

2. How does it connect to the natural and cultural environment? What elements are already present that you can highlight. What needs to go? What is your vision for how you want to use and enjoy your outdoor spaces?

3. Does it evoke a sense of place? Does it stir the emotions? What design, features, plants, and personal touches will give the garden its unique identity and personality?

As you answer these questions, you’ll find you have preferences about a lot of things. Use these as your guiding principles. Some will be clear at the outset, and others will evolve, says Bill. Guiding principles unique to you and your garden will be valuable throughout your process.

Some of Bill’s guiding principles included leaving the front of the house largely unchanged, and developing gardens behind the house that harmonize with the farmhouse’s architecture and take advantage of the distant mountain views.

He used old foundations for specific types of gardens. Where boundaries were needed, he used Lombardy Poplars to define the garden and help draw the eye upward. He says “it’s a gift to have a garden with so much sky.”

Other advice: Work with plants to screen out neighboring houses. He planted Norway spruce which formed a tall dense screen, and incorporated an orchard in the foreground to soften their looming presence.

He planted bold foliage plants within the ruined foundation of the old barn to show off the stonework.

He learned from other gardens and gardeners about making connections between designed spaces and the natural landscape. As a plant collector, he uses a wide variety of plants in his garden, even combining the perennial garden with the vegetable garden in the prime spot directly behind the house. He likes using sustainable and native plants as much as he can.

Bill freely admits he is a plant collector and that in his garden, plants—and trees—take center stage as the primary features of the landscape. He also likes to have something blooming all season (May to October), but notes that August to September is prime time when the garden is most alive with pollinators and butterflies.

Bill acknowledges that his garden is always evolving, and is never “done.” Maybe that’s because Bill gardens for his own satisfaction and sense of wellbeing—another guiding principle—but he loves sharing it with others and gauging the emotional impact it has on his guests.

Spend time with Bill Noble’s book, Spirit of Place, and you’ll come away with inspiration to create your own garden that is rich in context, personal vision, and spirit.

Spirit of Place: The Making of a New England Garden